5 – Room known as “di Garibaldi” – Chiarismo and the chiarismi

AUDIOGUIDA:

It was from this room that, on 27 April, 1862, Giuseppe Garibaldi appeared to the people to talk about the “homeland of arms and holy concord among free men”, as commemorated by the plaque placed outside by the Cremonese sculptor Francesco Riccardo Monti. Right in front of this hall stands the imposing body of the parish church that houses precious masterpieces such as Il Cristo risorto appare alla Vergine, a work from Titian’s period of maturity, and the group Compiantosul Cristomorto. Critics are divided over whether the latter should be attributed to Guido Mazzoni, known as Il Modanino, or a member of the Mantegnesco school. The route through the most important main theme of the collection leads fromthis section. If the story of the collection is a love story, the colour scheme of this story appears to be that of an artistic movement of the 1930s (but one that was not a true “movement”): Chiarismo.

“A crowd of young artists emerges from darkness and anonymity, already seasoned and experienced. Among these artists, who are getting a taste of fame for the first time, I would like to mention Umberto Lilloni. For four years now, he has pursued a path of solitary, absorbed ardour for his art, which has led him a long way, to very concrete and appreciable results”. These were the words Margherita Sarfatti used to present the art of these new artists, “skilled workers” who were conducting a “fierce battle, albeit silent and without parades, against the tastes and aspirations of neo-bourgeois painters”, as Edoardo Persico, Neapolitan critic and key theoretical figure for all the chiaristi, would later put it. There were five figures who launched this artistic season: Angelo Del Bon, Francesco De Rocchi, Umberto Lilloni, Cristoforo De Amicis, and Adriano Spilimbergo.

These new artists, seized by an “irrepressible poetic rapture” (in the words of Piero Torriano in La Casa Bellain 1932), strove for a primitive expression that should not, however, remain merely regret, nostalgia, and repetition. Sensibility, recollection, and melancholic loneliness seem to be the motives and forces common to an artistic koiné that never took definite shape as a “movement” or “group”, as others did through robust yet asphyxiating manifestos and labels. It is for this reason that we can say that, if an artistic moment defined as Chiarismo did exist, it did so because there were so many “chiarismi“, so many ways of conceiving and expressing a ” painting of sensitivity”, founded on the expressive possibilities of colour, that distanced itself from the Novecento movement and sentiments that played the major role in that period. “Here we return to flatness, to expressive deformation, to pure colour, to the irrational, the unconscious. Painting is meant to be self-centred, to refer to itself; to give voice to all that is more intimate and personal; to be reduced to raw, immediate, primal expression; to suggest with just a few inspired, sudden strokes, almost dictated in a dream. Beautiful things” (Piero Torriano). The term “chiarismo” was used for the first time in 1935 by the painter and critic Leonardo Borgese when reviewing the presence of the young artists Lilloni, Del Bon, De Rocchi, and Spilimbergo at the 6thLombard Trade Union Exhibition. It was then taken up by the writer Guido Piovene commenting on Lilloni’s individual exhibition at the Galleria Grande in Milan in 1939. The term was meant to describe the style of painting that replaced the plastic and volumetric values of the Novecento movement, the predominance of tonal and chromatic values in an intense lyricism of light and formal colour. The origin of this style was connected to a modality that Renato Birolli (a precursor of Chiarismo, along with Aligi Sassu) used in the late Twenties, applying “a thin layer of zinc white to a blank canvas […] While the white was still fresh, I painted on top of this layer, obtaining a bright, vibrant colour, almost like a fresco” (Renato Birolli). Although this technique was certainly not unique common to all the artists, it remains an important point of reference. As Elena Pontiggia recalls, “the problem of chiarismo is not the bright colour […] but the use of colour in an anti-plastic function, to the extent that the spatial elements are attenuated with two-dimensional effects”. Pontiggia always recognises two different paths with deep philosophical sentiments within this constellation: on the one hand, a lyricism with anxious, existential notes (Del Bon, De Rocchi, De Amicis, Marini), and on the other hand, a dimension suspended between fairy tale and dream (Lilloni, Spilimbergo, Facciotto). Here we find the minimal figures, disoriented existences, whose gaze is closer to the curious and insecure gaze of a child than that of a knowing adult.

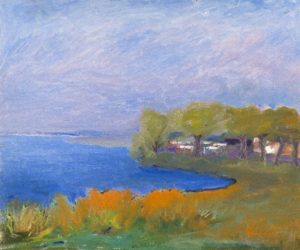

“Lilloni, who is above all a landscape painter, has the delicate, graceful, and enchanting style of an oriental painter on soft, transparent backgrounds: you could say that his manner is a sublimation of painting on silk or glass” (Guido Piovene).

In the art of Angelo Del Bon, in addition to his love for 19th-century avant-garde French painting, we also find an unprecedented and profound interest in oriental art and culture, and, in particular, in those clean and immediate Sino-Japanese prints.

Francesco De Rocchi perfectly summarises the poetics of these artists: “We eliminate […] the burdens of the Novecento movement, the dark lands and the bitumen; we open painting up to the source of natural light. Primarily, we open painting up to clarity of ideas, because chiarismo does not mean only painting with white, but a fusion of light and colour into form”.

Although Milan remained the centre and reference point of this artistic period, the Alto Mantovano area provided a fertile land for what would later be referred to as “Mantuan chiarismo“. Medole and the nearby Castiglione delle Stiviere formed a true development hub for a new, clear language, more marked by landscape and nature. The Castiglionese “scene” was founded in 1933 thanks to the joint work of Del Bon and Marini, who had met not long before in Milan through Lilloni (whose father was from Medole, where the artist often returned for long stays). Right from these very early years, this scene would function as an aesthetic laboratory capable of producing superb results. Giuseppe Facciotto, born in the nearby Cavriana, moved to Castiglione in 1917. Although it is not possible to limit his artistic research to Chiarismo alone, in the works exhibited here, we can identify that clear feeling expressed with a lyrical intensity that seems to have no equal among his traveling companions.

Carlo Malerba, born in Bastida Pancarana, in the province of Pavia, left his native land for Castiglione at just four years old. After graduating in Economics and Commerce in Rome, Malerba moved to Milan and began to frequent the artistic scene. In 1932, he painted with Lilloni in Medole and spent time with Del Bon in Castiglione. He spent long stays in our lands and it was here that he produced those works that Elena Pontiggia describes as “animated by a panicked sense of nature and at the same time shaken by a secret existential angst”.

Ermanno Pittigliani belonged to an even more limited and discreet group: that of the chiarist sculptors. While the most important figure was undoubtedly Broggini, Pittigliani (who also excelled in pictorial language), made his contribution thanks to a sculptural style that strove to distance itself from the static forms of the old artists of the time, proposing a convincing movement and freshness as shown by the two small heads in display here.

- Carlo Malerba, Burrasca, 1951